US border tax threatens Asian growth

Republican plan to penalise imports could upend region’s export-led economic model

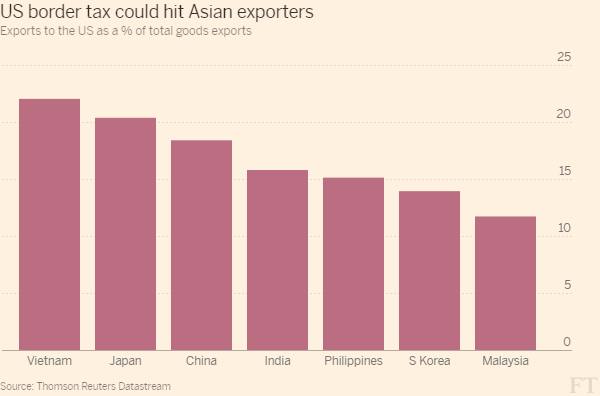

A border tax in the US could upend the export-based economic model that has brought prosperity to millions of people in Asia, say analysts, as the region wakes up to reforms proposed by Republicans in Congress.

Although most attention is still focused on whether president-elect Donald Trump will slap tariffs on China or target companies that move production offshore, proposals for a US tax regime that penalises imports could have a more permanent and far-reaching effect. “I think it would be a huge issue for Asia,” said Frederic Neumann, co-head of economic research at HSBC in Hong Kong. “It would also raise the spectre of retaliatory measures by other countries.”

Depending on how far a stronger dollar offset the change, a border tax could pull up the ladder climbed by developing countries from Japan to China and now Vietnam as they built industries based on exports to the US, forcing the region to seek a new economic model.

A variety of corporate tax proposals by Republicans in Congress would levy a “border adjustment” on imported inputs, while exempting exports from tax altogether. The structure is similar to a value added tax but because US companies could deduct their wage bills, the potential effect resembles a tariff on foreign goods.

Republicans such as Paul Ryan, the speaker of the house, have declared their opposition to Mr Trump’s threat of tariffs and have been pushing the tax reform instead, despite vehement opposition from US retailers and other import-dependent businesses. Pro-trade Republicans see it as a way to avoid a tit-for-tat trade war with China while also encouraging more manufacturing in the US.

Michael Gapen, chief US economist at Barclays in New York, said he had included tariffs on Mexico and China in his base case forecasts but there was “a 25 to 30 per cent chance we get border adjustments”.

Mr Gapen argued it was unlikely that appreciation of the dollar would fully offset the change and the impact would depend on how US trading partners reacted. They could change their own systems, launch a case at the World Trade Organisation or retaliate in other ways.

“The reason these plans call it a border adjustment is to try and avoid the backlash,” said Mr Gapen.

Worst hurt would be exporters of low-margin products, where little value is added in the US and demand is sensitive to price. That could include many goods sold by US retailers such as Walmart, where higher prices would probably lead to lower consumption, hitting their makers.

“I would single out the highly trade-dependent economies like [South] Korea, Taiwan, China to some extent, Malaysia and Vietnam,” said Mr Neumann. “India, Indonesia and the Philippines would be less exposed.”

Mr Neumann highlighted a further issue: even if a border adjustment were offset by a strong rise in the dollar, it could lead to a renewed round of tension over currencies, even if Asian countries resisted the temptation to intervene to protect their economies during a transition.

In contrast to tariffs that target a particular country such as China, a border tax would affect imports from countries in the North American Free Trade Agreement, hitting even carmakers that have localised some production in Canada or Mexico.

“It appears the proposal for a new tax code will be punitive to imported cars and content from any nation,” noted Deutsche Bank analyst Kurt Sanger. “We need to redefine our views on import ratios to include Mexico and Canada.”

Japanese carmakers are well advanced in localising production to North America but most have put some capacity in Mexico or Canada. Imports make up 34 per cent of the cars Honda sells in the US, while the figure is 45 per cent for Nissan, 50 per cent for Toyota and 100 per cent for Mazda, according to Deutsche.

The figures are 41 per cent for Hyundai and 63 per cent for Kia, although that production comes from their home base in South Korea, rather than Mexico or Canada, so the potential pain for the national economy is larger.

All would be hurt by a US border tax, although the real burden depends on how much of the final product was made in the US. According to Mr Sanger, the Japanese companies are generally better off than the South Koreans, and no worse off than US rivals, given the heavy reliance of the latter on production in Mexico.

Source: www.ft.com

Comment here